Fluids Simulation

Professional Bootstrap Template

Fluid simulations, at the current time, mostly use algorithms like the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) that are computationally expensive. In our project, we implement an algorithm belonging to the Position Based Dynamics framework, that takes a particle-driven approach to the simulation of fluids as outlined in the paper of Macklin and Müller. More specifically, we implemented the fluid as a collection of particles subject to incompressibility constraints and separately update the position of these particles after accounting for vorticity confinement and viscosity. In the end, we created animations of a body of fluid that appeared realistic without needing to resort to small intervals of the time step.

|

We will compare the efficiency of our algorithm to that of the Smoothed-particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) algorithm. The SPH algorithm, a widely used computational method for simulating fluid flows, adheres to the time step limit imposed by the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) condition shown below. In the equation below, h is the global support radius, c is the velocity of sound propogation in the fluid (related to stiffness), k is the stiffness constant and alpha is just a constant.

|

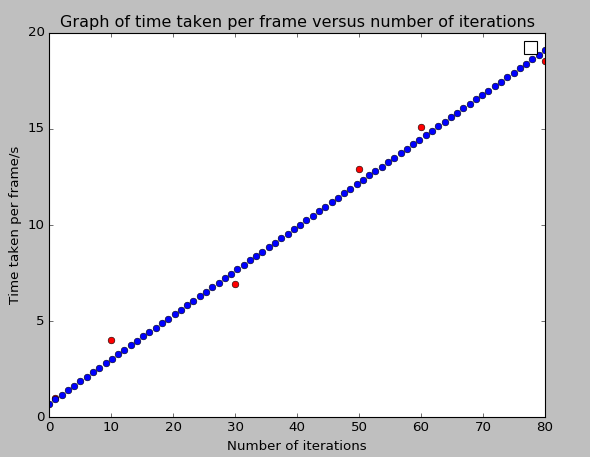

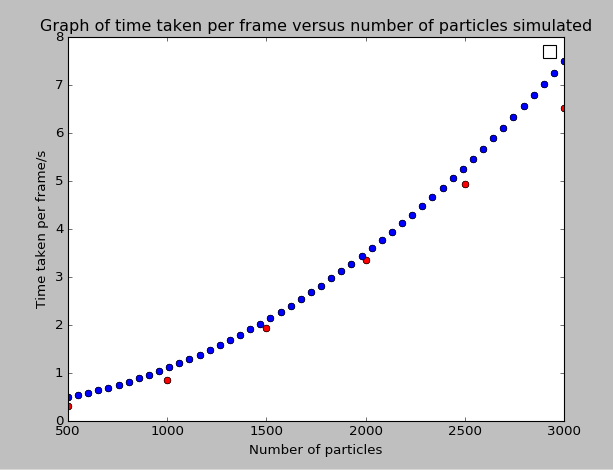

Based on the structure of the algorithm, the runtime increased linearly with the number of iterations and polynomially with the number of particles we were modelling. The iterations in point refer to the iterations of the position update within each frame. The position updates are necessary so that the final image rendered reflects the accurately the positions of the particle. We found that the images generally converged to an accurate one at 5 iterations. An image of the pseudocode is shown at the bottom. This can be seen in the graphs below.

|

|

On top of generating the intended animations, we thought it would be fun to play around with the different parameters. The animations of each along with the parameter varied are shown below.

1) The following gif is with 1 iteration. You can see that there is a lot of clumping and violation of rest density constraints. If more iterations were allowed, it would have updated correctly.

2) The following gif is with a low rest density. It behaves somewhat like a gas.

3) The following gif is with a low value of the smoothing radius for the kernel enforcing incompressibility constraints. It is well-behaved initially because the radius is small and particles are far apart enough. Once they get close enough though, the particles go crazy trying to fulfill the constraints.

4) The following gif is with a low value of gravity. The cube of water forms into a sphere (most stable configuration) before falling and even after it falls, it doesn't really flow because of the comparatively higher viscosity.

5) The following gif is with a large time step of 1. The animation loses a lot of its finer details. For instance, the splash isn't quite as dramatic because the time over which the position updates are much longer and hence, several intermediat movements are not captured.

1. Lagrangian Fluid Dynamics Using Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics by Micky Kelager, January 9 2006

2. Position Based Dynamics by Muller et. al, Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, April 2007

3. Position Based Fluids by Miles Macklin and Matthias Muller

4. Simulating Gaseous Fluids with Low and High Speeds by Yue Gao et. al, Pacific Graphics 2009

5. Time Adaptve Approximate SPH by Prashant Goswami and Renato Pajarola, VRIPHYS 2011

Patrick Lutz

1. Implemented viscosity

2. Implemented incompressibility constraints (find_lambda, kernel functions etc)

3. Wrote final report and plan for final project

4. Implemented vorticity

5. Generated animations for the animation with larger number of particles and fine-tuned the parameters

Leah Tom

1. Implemented collision detection

2. Implemented vorticity in parallel

3. Wrote final report and plan for final project

4. Implemented moving wall

5. Generated animations with different values of parameters for smaller number of particles